Time is a weapon wielded by the rich, who have excess of it, against the rest, who must trade every breath of it against the promise of another day’s food and shelter. What kind of world have we made, where human beings can live centuries if only they can afford the fix? What kind of creatures have we become? The same as we always were, but keener.

In the ancient heart of Oxford University, the ultra-rich celebrate their vastly extended lifespans. But a few surprises are in store for them. From Nina and Alex, Margo and Fidget, scruffy anarchists sharing living space with an ever-shifting cast of crusty punks and lost kids. And also from the scientist who invented the longevity treatment in the first place.

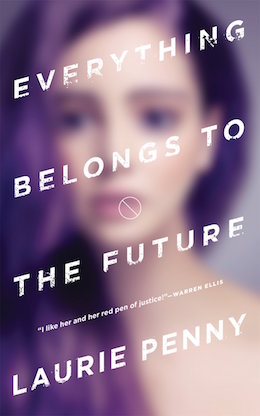

Laurie Penny’s Everything Belongs to the Future is a bloody-minded tale of time, betrayal, desperation, and hope—available October 18th from Tor.com Publishing.

Letter from Holloway Prison, December 5, 2098.

Dear Daisy,

We were never really friends, were we? Somehow, though, you’re the person I want to write to most in here. I hope these letters get to you. I’m giving them to Alex, who I am absolutely sure is reading them too, and although they aren’t for meant for him, I hope he gets something instructive from them.

Hello, Alex. I hope you’re well. I hope you’re safe. I hope you understand that you are not forgiven. Even after the awful, terrible thing we did. Even after the time bomb, and everything that came afterwards. I can’t let it go. The anger keeps me sharp. Keeps my brain from turning to paste. It’s that or the crossword, and rage is more reliable. I am sorry about your hands, though.

Anyway. I’ve got a story for you, this time. For both of you, as it happens.

Have you heard the one about the Devil’s bridge?

It’s an old story, and there are lots of different tellings, but it goes something like this.

A carpenter wants to build a bridge across a river. Not just any bridge, but the strongest, sturdiest bridge that has ever been made or thought of, to take him and his wife to the far bank, where there are treasures whose nature is unimportant to the story. Let us assume that he has good reasons for wanting to get there, or thinks he does. Let us assume that his tools and skills are insufficient to the task. Let us assume that he is out of options and ideas.

He sits down on the plain, grey bank he calls home and makes a wish.

Instantly there appears before him a handsome man with savage eyes and shining hair, and his clothes are rich and strange and he blinks less than a person ought to, and the carpenter knows that this is the Devil.

I can build a bridge for you, says the Devil. I can build you a bridge across the wild, wide river, and it will be the greatest bridge ever seen, the strongest, the most magnificent. It will stand for a hundred years, and people from all around will come to walk on it and say: the man who made this must be a fine carpenter indeed. The bridge will draw visitors from seven counties. Boys will take their sweethearts here to propose. You can charge an entry fee. You can open a hot-dog stand. Whatever you want.

I’m not really interested in that, says the carpenter. I just want to get to the other side.

Well, says the Devil, that’s part of the package.

What would it cost me? Says the carpenter.

Alright, I don’t have a lot of time left to write. They come in and stop me at guard change.

Meanwhile: consider that time is a weapon.

Before the coming of the Time Bomb, this was true. It was true before men and women of means or special merit could purchase an extra century of youth. It has been true since the invention of the hourglass, the water clock, the wrist watch, the shift-bell, the factory floor. Ever since men could measure time, they have used it to divide each other.

Time is a weapon wielded by the rich, who have excess of it, against the rest, who must trade every breath of it against the promise of another day’s food and shelter. What kind of world have we made, where human beings can live centuries if only they can afford the fix? What kind of creatures have we become?

The Time Bomb. Aerosolised Gerontoxin. Currently being deployed around a world in panic by desperate people with nothing to lose and nothing to make but their point. You know you could have stopped it. Alex, I’m talking to you now. You could have stopped it all from happening. Maybe someday soon I’ll tell them how. After all, so much life has been wasted.

So very much life.

* * *

There was a wall. It was taller than it seemed and set back a little from the street, so the ancient trees on the college side provided a well of darker shadow, away from the streetlights.

The wall was old and rough, ancient sandstone filled in with reinforced cement to keep out intruders. The drop on the other side landed you in thick grass. Still, Alex was afraid of the wall. Of the idea of it.

Nina was the first to make the climb. She squatted on top of the wall, an implike thing in the darkness. Then she turned and held out her hand to Alex, beckoning.

‘You have to see this,’ she said.

Alex started to climb the wall between the worlds. The old stone bit at his hands. Halfway up, he heard Nina made a little sound of disappointment in her throat. He was never fast enough for her.

The approach to Magdalen College was across the deer park.

That was where they were going: through the park, avoiding the dogs and the security lights, into the college, into the ball all sparkling under the starlight.

It was four of them, Nina and Alex, Margo and Fidget, and they were off to rob the rich and feed the poor. An exercise, as Margo put it, as important for the emotional welfare of the autonomous individual as it was for the collective. Margo was a state therapist before she came to Cowley, to bunker down with the rest of the strays and degenerates clinging to the underside of Oxford city. Five years of living off the grid hadn’t cured her of the talk.

At the top of the wall, Alex unfolded himself for an instant, and then he saw it-—what Nina had been trying to show him. The old college lit from behind with a hundred moving lights, butter-soft and pink and pretty, a bubble of beauty floating on the skin of time.

‘It’s beautiful,’ he said.

‘Come on,’ said Margo, ‘get moving, or we’ll be seen.’

Margo was beside him now, the great bulk of her making no sound on the ascent. Alex’s mouth had been dry all night. He licked his teeth and listened to his heart shake the bars of his ribcage. He had promised the others that he was good for this. He wasn’t going to have another anxiety attack and ruin everything.

‘As your therapist,’ said Margo, gentling her voice, ‘I should remind you that God hates a coward.’

Alex jumped before she could push him, and hit the grass on the other side of the wall without remembering to bend his knees. His ankles cried out on impact.

Then Nina was next to him, and Margo, all three of them together. Fidget was last, dropping over the wall without a sound, dark on dark in the moonlight. Margo held up a hand for assembly.

‘Security’s not going to be tight on this side of the college. Let’s go over the drill if anyone gets caught.’

‘We’re the hired entertainment and our passes got lost somewhere,’ said Nina, stripping off her coverall. Underneath, she was wearing a series of intricately knotted bedsheets, and the overall effect was somewhere between appropriative and indecent.

Alex liked it.

‘Alex,’ said Margo, ‘I want to hear it from you. What are you?’

‘I’m a stupid drunk entertainer and I’m not being paid enough for this,’ Alex repeated.

‘Good. Now, as your therapist, I advise you to run very fast, meet us at the fountain, take nothing except what we came for, and for fuck’s sake, don’t get caught.’

Fireworks bloomed and snickered in the sky over the deer park. Chill fingers of light and laughter uncurled from the ancient college. They moved off separately across the dark field to the perimeter.

Alex squinted to make out the deer, but the herd was elsewhere, sheltering from the revelry. The last wild deer in England. Oxford guarded its treasures, flesh and stone both.

Alex kept low, and he had almost made it to the wall when a searchlight swung around, pinning him there.

Alex was an insect frozen against the sandstone.

Alex couldn’t remember who he was supposed to be.

Alex was about to fuck this up for everyone and get them all sent to jail before they’d even got what they came for.

Hands on Alex’s neck, soft, desperate, and a small firm body pinning him against the wall. Fidget. Fidget, kissing him sloppily, fumbling with the buttons on his shirt, both of them caught in the beam of light.

‘Play along,’ Fidget hissed, and Alex understood. He groaned theatrically as Fidget ran hard hands through his hair and kissed his open mouth. Alex had never kissed another man like this before, and he was too shit-scared to wonder whether he liked, it, because if they couldn’t convince whoever was on the other end of that searchlight that they were a couple of drunks who’d left the party to fuck, they were both going to jail.

The searchlight lingered.

Fidget ran a sharp, scoundrel tongue along Alex’s neck. A spike of anger stabbed Alex in the base of his belly, but instead of punching Fidget in his pretty face, he grabbed his head, twisted it up and kissed him again.

The searchlight lingered, trembling.

Fidget fumbled with Alex’s belt buckle.

The searchlight moved on.

Fidget sighed in the merciful darkness. ‘I thought I was going to have to escalate for a second there.’

‘You seemed to be having a good time,’ said Alex.

’Don’t flatter yourself,’ said Fidget, ‘The word you’re looking for is “thanks”.’

They were almost inside. Just behind the last fence, Magdalen ball was blossoming into being. Behind the fence, airy music from somewhere out of time would be rising over the lacquered heads of five hundred guests in suits and rented ballgowns. Entertainers and waitstaff in themed costumes would be circling with trays of champagne flutes. Chocolates and cocaine would be laid out in intricate lines on silver dishes.

Alex and the others weren’t here for any of that.

They were here for the fix.

Excerpted from Everything Belongs to the Future © Laurie Penny, 2016